CIVILIAN BRIDLES

OF ANTEBELLUM AMERICA

By Ken R Knopp

As artifacts, 19th century civilian (non-military) bridles are very difficult to identify. Their common appearance and similarities in pattern and materials throughout the late 18th, the 19th and early 20th centuries often render exact dating of them nearly impossible. More importantly or sadly, few examples remain. More of a tool, the bridle unlike a saddle, lacked sentimental value that would have made them keepsakes. Exposure to the elements, hard usage and difficulty in caring for them often relegated them to the corner of the barn where they dry rotted until eventually thrown away. The bit might be kept but few early civilian bridles have survived. As a result determining their common Antebellum appearance presents a problem.

Civilian bridles of the period came in two basic types- those for coach (or buggies) and wagon teams and, those for riding. Riding bridles differed greatly from coach or wagon bridle patterns that tended to be more durable, decorative and have (but not always) blinders. Our study here will focus primarily on those for riding. While there is a lot of great post war information and illustrations about civilian bridles to be found, those from the early 19th century and even war time era are few and far between. Photography was not widely available until the 1850’s and quality photographs of horses exceedingly more rare. Military patterns provide some guidance as do paintings and drawings but without other decisive documentation such as museum records or family history dating an otherwise period bridle is often speculative at best.

PHOTO # 1: Fancy coach or team bridle. Note the fancy face piece, tassels, skillful sometimes colored leather work and stitching. The winkers (a.k.a. blinders) were round or oval for coach bridles and often had brasses, fancy monogram stitching or the owner’s initials. For light buggy or road harness (wagon teams) the winkers were generally more plain and squared. Most team bridle bits had different mouthpieces than riding bridles (rarely using a port but rather a snaffle or straight bit) but for coach and buggies, the cheeks of the bit were often equally as ornate as the bridle- all meant to illustrate the wealth of the owner. 1875 Harness Maker’s Manual.

PHOTO # 2: Very common men’s riding bridle headstall of the period. Note the cast iron “wire” horse shoe buckles which were probably the most common bridle buckle of the pre war 19th century. They were easy to make and found on all types of early civilian, military and Confederate bridles as well as other applications. Photo by author courtesy the Atlanta History Center.

PHOTO # 2: Very common men’s riding bridle headstall of the period. Note the cast iron “wire” horse shoe buckles which were probably the most common bridle buckle of the pre war 19th century. They were easy to make and found on all types of early civilian, military and Confederate bridles as well as other applications. Photo by author courtesy the Atlanta History Center.

Nevertheless, there are methods. Period harness maker’s manuals are tremendously revealing as is identification of their appearance through their patterns and “Lorinery” (hardware) components. The most obvious of these, bridle bits, are often questionable however because they were sometimes detachable. Yet, certain types of buckles and rivets can be quite useful. In summary, for a better understanding of period bridles we must therefore rely on all of the above evidence and thankfully, include the valuable contributions provided by relic hunters. 1.

The purpose of the bridle was simple: to hold the bit and effect its use to control the horse. Riding bridles as a utilitarian tool have remained virtually the same for centuries consisting of two cheek pieces, a crown piece, often a brow band and occasionally (usually on military or coach horses) a nose band. Nineteenth century civilian bridles were in fact, not much different from the earlier patterns except in bit deployment and materials.

In general, the Antebellum riding bridle took its name from the style of bit attached to it such as “plain snaffle”, “Port”, “Pelham” or, “Port & Bradoon” bridle. The basic headstall included a crown piece, two cheek pieces with or without billets and buckles, front piece (brow band), throat latch and reins. All being made up most often in matching materials. Two basic riding bridle patterns were employed. A “plain” bridle headstall that held a single bit and, the very popular double cheek bridle that employed two bits- a port bit and a bradoon bit. However, another popular variation of the plain bridle was the “halter-bridle” which combined the bridle and halter as one with the capacity for easily removing the bit. While often employed in the military its civilian use was well known in the period too. In the early to mid-19th century the common men’s riding bridle were much less varied in character than that found on military, coach or ladies bridles. Yet by late in the century these lines were considerably more blurred. Ornamentation consisted principally of cross face pieces, tassels and brass work. 2. So, what were the materials of the bridle headstall?

PHOTO # 3: Double Cheek Port & Bradoon Riding Bridle. Two bits were used- a port for more control and a snaffle for light use. This type bridle was very common to the period both in civilian and military use.

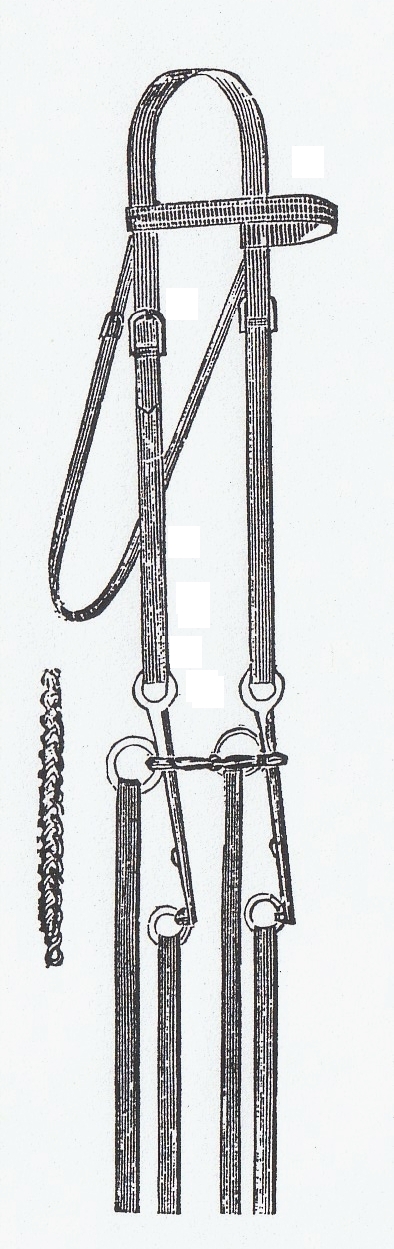

PHOTO # 4: “Plain” Pelham Bridle. Antebellum riding bridles were usually named for their bits. This “Plain” bridle headstall employs a double rein Pelham bit (similarly effective as the double bit ” Port & Bradoon”) and metal curb chain typical of the pre war period.

PHOTO # 4: “Plain” Pelham Bridle. Antebellum riding bridles were usually named for their bits. This “Plain” bridle headstall employs a double rein Pelham bit (similarly effective as the double bit ” Port & Bradoon”) and metal curb chain typical of the pre war period.

Leather had been in common use for this item for centuries and of course, by the 19th century was still the most dominant material. Three kinds of leather were generally used for bridles- black harness, russet bridle leather and buff. Light weights were always used, with the cheek pieces and reins cut from the firmest part of the leather side. English russet was most preferred. Buff leather was only used when matching to saddle seats or knee pads of rough out or buckskin. Beyond that, the use of leather in wide ranging cuts, stains and finishes such as round, layered, waxed, enameled, patent, etc. was as variant as the owners personal desire for the bridle’s appearance and only limited by the ability to make it and cost. 3. Other, more economical indigenous materials were also in common use especially on the frontier such as rawhide, woven horse hair, Spanish Moss, rope and even bark. Round leather and gilded cloth was very popular at this time as was newer materials coming into the common realm like cotton webbing for inexpensive, plain bridles. One fairly consistent factor was the width of the material. Bridles had to be strong and sturdy to fit and hold a variety of bits (and buckles). As a result, whatever the materials employed the width ranged from ½ inch to one inch but the “standard” width of the cheek pieces tended to be 3/4’s of an inch. 4.

The stitching of the leather, either in general or, of buckles and other components was hand sewn at six to ten stitches per inch and often using hand spun thread. Even during the war, it was rare for a sewing machine to have been used but it did become more common late in the century. Hand sewing can be distinguished from machine by carefully viewing and measuring the consistency of spacing between holes. Copper rivets were rarely used on bridles before the war and split (tubular) rivets were a post war (1870’s) invention.

Hardware or buckles, are another good method in identifying or dating a bridle. Illustrations and surviving descriptions of those available in harness shops of the period are very telling. Being expensive, brass buckles of various patterns were popular on more “high-end” bridles as was occasionally leather covered (hand sewn) buckles. While iron, cast and finished with paint, japanned or hand forged, was more common on the “everyman” bridle. Again, those in use at the farther reaches of civilization often did not use buckles but employed the materials at hand in the form of latigo ties and buttons. Buckle patterns varied widely in styles such as sunk-bar, frame, horseshoe either of cast iron or brass, often they were hand forged. Roller buckles were increasingly common during the period too. They may go back as far as Medieval times but the means to mass produce them in America was not in common use until just prior to the Civil War. Excavations by relic hunters over the years have thankfully provided us with surviving examples of many of these buckles. 5.

One of the more colorful aspects in the appearance of 19th century civilian bridles were their decorative enhancements which were by design an indication of social status. This was particularly true of coach and buggy bridles. Wagon bridles could be decorative but were generally more plain and durable than coach bridles where there was a lot of opportunity for the skilled harness maker to exercise design, embellishment and taste. However, for men’s riding bridles, especially those in the east, the plain, conservative, Puritan/Victorian bent of 19th century American society was clearly dominant. As noted above bridle hardware such as the type buckles used had their popular styles of the day but other indulgences of individual taste for men’s riding bridles were generally restrained to that of fancy stitching and rosettes. For example, brass or other variant rosettes were typical to the common bridles while fine leather (often layered) rosettes to high-end men’s bridles. Other more fanciful add-ons such as tassels and face cross plates were limited to military bridles, ladies dress bridles or, the upper class and their team equipment as a means to illustrate their wealth. 6.

PHOTO # 5: Ladies Dress Bridle Headstall (without bit) Note the fancy tassel, combination of round and flat leather and, rosettes employed to suggest a graceful feminine touch, wealth or both.

On the other hand, farther west there appeared to be less constraint and, often a certain geographic flair. For example, in Texas or the far west, Indian influences could be found in the use of feathers, horse hair and beads or, a strong often gaudy, Spanish influence with colorful designs of braided leather, cloth, horse hair, silver plates and conchos. Nevertheless, there can be no doubt decorative embellishments of early 19th century civilian bridles were limited by social proprieties, a lack of exposure, access to materials and financial costs. 7.

In summary, bridles from the Antebellum period differed widely but had important functions and characteristics. Coach and buggy bridles differed from wagon (road harness) bridles; the three from riding bridles; men’s bridles from ladies bridles and all in material, hardware and style. While clearly well known and accepted at the time these differences reflected their purpose and the social structure of the period in ways much less obvious and understood today.

APPRECIATION: The author wishes to dedicate this article to….my great friend John Ashworth. God Bless him! Thanks goes to my buddy David Jarnagin (always) for his leather expertise, Patrick McAlister for the inspiration and my surgeon Dr James Antinise for neck surgery which afforded me the time off to research and write this article. Lets not do that again!

PHOTO # 6: T.J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s horse “Little Sorrel” and his bridle. The use of rings was a common 19th Century bridle configuration. Note the round leather and buckles employed. Photos by author courtesy the V.M.I. Museum, Lexington, Va.

Fancy Bridles with face pieces and tassles.

PHOTO # 7: CS Gen. Patrick Cleburne’s bridle reputedly a pick up from the battlefield of Franklin. Note its round leather cheek pieces, sunk-bar frame buckles and rosettes. The bit is a straight-bar snaffle wagon (mule) bit, not a typical riding bit and therefore not likely original to Gen. Cleburne’s use of the bridle. Photo courtesy the Museum of the Confederacy, Richmond Va.

PHOTO # 8: Common Antebellum Civilian Bridle &Harness Buckles: Many variations exist in brass and iron.

Top Row, L – R

1. Early Hand Forged Square buckle

2.-3. Fancy 18th Century Scotch brass harness or gear buckles

4. “Spade” buckle of brass.

5. Beveled iron buckle with very common brass sheathing.

Middle Top Row, L- R

1. Flat Top Turned Up buckle, (aka “Band” buckle)

2. Sunk Bar “Conway” buckle of brass. Late 19th century military versions were somewhat different.

3. Sunk Bar frame buckle with “crown” top.

4. Oval Sunk Bar Frame Buckle.

Middle Bottom Row, L- R:

1. Very common 18th-19th Century cast iron (or brass) horse shoe buckle sometimes called “Wire Bridle” buckles. 2. Crescent Buckle (aka Philadelphia,or Union Buckles)

3. Cast Brass Horseshoe. These were very common civilian and military buckles made of either brass, brass sheathed or iron.

4. Cast brass beveled buckle variation.

5. Fancy buckles were often leather covered. This is an imitation

leather covered buckle of cast iron.

Bottom Row, Roller buckles. Early 19th century “wire” rollers were machine formed and often had hand forged tongues. L- R:

1. Roller buckle of square stock from Mexican War battle of Buena Vista.

2. Square “wire” Roller.

3. “Barrel” “wire” Roller Buckle.

4. Common cast iron roller buckle.

PHOTO # 9: While modern examples the concept is the same- to mount the bridle headstall or reins without the use of a buckle. On left is a leather “button” and right, a latigo tie. Both came in many forms during the period.

PHOTO # 11: Civil War Federal Draught Harness (Wagon) Bridle with its original bit. Many tens of thousands of these were made by the Quartermaster and Ordnance Dept.’s for issue with wagon team harness. Very few survive today. Photo by author courtesy the Atlanta History Center.

FOOTNOTES:

1. The Harness Maker’ Illustrated Manual, A Practical Guide Book for Manufacturers and Makers of Harness, Pads, Gig Saddles, etc., W.N. Fitzgerald, New York, 1875. Reprinted by North River Press, 1975. Pgs. 183-204. Saddlery and harness making had not changed much in the 100 years prior to the publication of this book so the information about leather, saddlery patterns and hardware found therein is invaluable and, much as it was during the Antebellum period. However, shortly after its publication great changes began to take place. In the 1870’s oak bark as a tanning agent began to be replaced by both Hemlock and gradually, South American Quebracho bark which became extensively used by the turn of the century. Then in 1904 a blight destroyed the Chestnut Oak trees in the United States ending forever the use of that kind of bark as a tanning agent. In the 1880’s leather bartering was changed so as to be sold by the square foot instead of by weight altering many of the processes in leather tanning and production that were designed to induce weight. Furthermore, in the decades that followed the war new machines were invented for sewing heavy leather, splitting and cutting leather, new metal alloys for buckles and, new rivets and machines for mass producing them evolved quickly so that by the early 20th century leather tanning, manufacturing and their products were noticeably different in appearance than that of Antebellum America.

Johnson, Drew H., Eymann, Marcia, Silver & Gold, Cased Images of the California Gold Rush. University of Iowa Press for the Oakland Museum of California,1998.Pgs, 94, 146, 172

2. The Harness Maker’ Illustrated Manual, A Practical Guide Book for Manufacturers and Makers of Harness, Pads, Gig Saddles, etc., W.N. Fitzgerald, New York, 1875. Pgs. 183-204.

Malm, Dr. Gerhard A., DVM. Bits & Bridles Encyclopedia, Valley Falls, KS: Grasshopper Publishers, 1996. Pgs. 446 465.

Study of popular trends, evolution and manufacturing details of saddlery from a compilation of original and reprinted 19th and 20th century saddle catalogs hereafter referred to as “The Catalogs”, including: Harbison & Gathright, Louisville, Ky. 1875; JT Gathright & Look Louisville, KY. 1879; Decamp, Levoy Saddle Company, Cincinnati, Oh. 1876. Eugene, Or: (Collectors Library, 1997, www.rsdmilitaria.com); Miller, Morrison & Co. NYC, NT, 1880; Riser & Eritz, Co. Chicago, Ill. 1882; Peters & Calhoun Co. Newark, NJ & NYC 1883: C.J. Cooper & Co. Chicago, Ill. 1885; Perkins Campbell, Cin. Oh. 1888; Jacob Strauss Saddlery, St. Louis, Mo. 1887-1899; D. Mason & Sons, LTD. Walsall/Birmingham England, 1880’s; Graf, Morsbach & Co. Cin. Oh. 1890; S.R. & J.C. McConnel Saddlery, Burlington, IA. 1893, (Collectors Library, 1997); Moseman’s Illustrated Guide for Purchasers of Horse Furnishing Goods, Catalog of 1889. Charles Kaufman and Bracken Books, 1976; New York: Cresent Books, 1990. Sears Roebuck 1902, 1906 & 1908; Lerch Bros. Saddlery, Baltimore, MD. 1904; English Edwardian Goods, London, NYC, Washington, 1907; Victor Marden, Dalles, Or. 1917; Mehlbach Saddle Co. Successors to the Whitman Saddle Co. 1919, (Collectors Library, 1997); Perkins Campbell Saddlery, Cinn. Oh. 1925; Francis Bannerman Catalogue of Military Goods, 1927. (Northfield,Ill: DBI Books, 1963). Hereafter, referred to as “The Catalogs”.

3. The Harness Maker’ Illustrated Manual, A Practical Guide Book for Manufacturers and Makers of Harness, Pads, Gig Saddles, etc., W.N. Fitzgerald, New York, 1875. Pgs. 183-204.

4. IBID.

5. Knopp, Ken R., Made in the C.S.A. Saddle Makers of the Confederacy, Self published, 2003.

Files of the firms of dozens of firms that provided buckles and hardware to the Confederate Ordnance Department. Firms having contracts or business with the Ordnance Department for the manufacture of equipments during the war, M346, Confederate Papers Relating to Citizens or Business Firms, National Archives, Washington DC.

6. The Catalogs. W.N. Fitzgerald, New York, 1875. Pgs. 183-204.

The Harness Maker’ Illustrated Manual, A Practical Guide Book for Manufacturers and Makers of Harness, Pads, Gig Saddles, etc.,

Malm, Dr. Gerhard A., DVM. Bits & Bridles Encyclopedia, Valley Falls, KS: Grasshopper Publishers, 1996. Pgs. 446 465.

Johnson, Drew H., Eymann, Marcia, Silver & Gold, Cased Images of the California Gold Rush. University of Iowa Press for the Oakland Museum of California,1998.Pgs, 94, 146, 172

7. Man Made Mobile, Early Saddles of Western North American. Ahlborn, Richard E. ed. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1980. Pgs. 39 – 71.