By David Jarnagin and Ken R Knopp (originally published in the Journal of Military Historians)

Historians, collectors and reenactors are well aware that mid-19th century Federal military regulations required most leather equipment and accouterments to be dyed black in color. But why? And, just how was it done? Moreover, if black was the finish color of regulation then why do surviving Civil War time accouterments display a wide variety of colors from black to chocolate brown? How did that happen? One might naturally fault military leather contractors, inadequate dyes or possibly the effects of time on these artifacts. However, the real answer to all of these questions is more interesting, chemically complex and often cloaked in the secrecy of ancient artistic privilege.Long before the leather was dyed and finished an intricate, laborious, multi-step process of approximately six months was required to tan the animal hide into leather. In the 19th century the “vegetable tanning” method was more commonly used and achieved by repeat soakings of the raw hide in solutions made from the bark of trees mixed with natural and other ingredients which generate an acidic chemical reaction that slowly turns the hides into leather. The “tannin” (tanning agents) found in the bark is the central ingredient that preserves the hide- first by stopping natural decay then leaving the leather both flexible yet durable enough for extended use. Bark taken from Chestnut Oak and Hemlock trees were the two most commonly used by American tanners of the time. Chestnut Oak (oak tanned) leather was mandated by the Federal War Department during the war because of its more acidic nature which aided the tanning process and perhaps more importantly, for its ability to bond with and hold the black leather dyes.

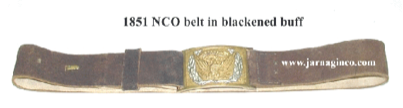

All leather intended for military equipment construction was dyed and finished at the tannery during the tanning process. For military usage two types of leather were provided by contract tanneries to both the government and to private accoutrement suppliers and used in making cartridge boxes, cap pouches, belts, bayonet scabbards and horse equipment- “sleeked” (vegetable tanned leather dyed black on the “grain” or smooth side of the leather) or, “buff” (“mineral”tanned then dyed black or white on the “rough” or “flesh” side of the leather). White buff was used extensively by the military through the Mexican War. In the 1850’s the army had trouble getting buff in any color so in 1858 they switched to black “waxed” leather (leather finished over the rough or flesh surface side) for its belts and slings. For most other Federal “war time” leather accoutrements (cartridge boxes and cap boxes) “bridle” leather was usually used and finished (“sleeked” or “jacked”) on the grain (smooth NOT rough) side. Black buff leather was still made for belts and slings but did not make up a large part of Federal accoutrement production. (See Text Box # 1)

|

|

|

|

“Buff” leather of white or black was not vegetable tanned. The grain surfaces were sanded or “buffed” prior to having the dye finishes applied. Above right is an 1851 NCO belt of blackened (albeit faded) buff. To the right is an 1844 belt of white buff. |

Black was the color of regulation by the Federal Ordnance Department for several reasons. First, the early influence of European armies, especially the French who used black accouterments, cannot be over looked. On a more practical note, black will hide stains to the leather, was easier to clean and could be buffed to an attractive shine. Most important, leather finishes such as dyes were used to help stop the damaging effects of wetting and drying from constant exposure to the elements inherent with the service of military equipment.

So, how was leather dyed black? Historians have naturally assumed the formula found in the 1861 Ordnance Manual was the pervasive recipe for military equipments. However, this formula was never meant for dyeing sleeked leather. It in fact, lacks the necessary ingredients to chemically bond the tannin to turn vegetable tanned leather to black. In practice, this recipe was only intended as a re-blacking or touching up formula for mineral tanned buff leather and in effect, little more than a good quality black ink.

The use of the word, “dye” is a bit misleading too. In actuality, the process of coloring vegetable tanned leather to black is a chemical reaction between iron mordants, logwood and the tanning agent used in leather during the tanning process. Iron mordants are particles of iron often mixed with mild acids such as vinegar. Logwood is vegetable matter that acts as a natural dyeing agent to get the blue black iron mordants to turn a deep, rich black. Tanning agents are residue from plants essential in the process to preserve hides into leather. As noted above, for most military usage leather this tanning agent (in vegetable tanning) was usually the bark from oak trees. Careful and often secretive preparation of the leather at the tannery including the right balance of the above ingredients, will determine the quality of both the leather, the black color and how long each will last. 1.

After the long laborious bark tanning of the hide, the leather was then “finished” which included various additives, polishing and usually, staining or dyeing. To dye black leather, “curriers” (tannery specialists) generally used two basic dye formulas and a multi-step preparation process often enhanced with their own secret ingredients and methods. One of these recently re-discovered basic dye formulas consisted of “scraps of old rusted iron (are) deposited in a deep vessel and covered with sour beer, which is allowed to act upon them for three months. A red liquid is thus formed, which is a solution of acetate of iron. Another liquid may be made use of, which is less expensive and requires less time in the preparation. Sour beer is mixed with yeast from barley, and after twenty four hours, is added to a solution made by boiling copperas in vinegar, care being taken first to remove all the yeast from the surface. A mixture of solution of sulphate and of acetate of iron is thus formed.” 2.

Using this formula or similar ones, the curriers then applied the dye to the leather, “while still on the table, being moistened before this operation, if it has become too dry, since a certain degree of humidity is necessary to enable it to receive the color. For this purpose, a mop of wool, or brush of horse-hair, is dipped in the (dye) composition prepared for the purpose,, and the hair side (smooth side of the leather) is thoroughly rubbed with it in every direction. Two applications of black are generally required for sleeked leather, and when any parts of the surface remain a red color, even a third may be requisite. When the leather is of a fine black color and perfectly dry, it is exposed to the action of a press for a time not longer than two weeks during which it is increased in density and firmness, the excess of tallow being forced out from it. …. A polish is given with sour beer or barberry juice, and the surface is slicked with a very smooth stretching iron or a lump of smooth glass.” . If any spot of grease or defects of surface remain, the parts which are thus deficient are gently rubbed with a cloth dipped in polishing liquid, until they become perfectly bright. 3. This process gives the leather a fine black surface and a good luster though not as highly polished as “patent” leather but a good shine nonetheless.

Dying leather black was a precise process requiring great skill. Since the tanner was essentially working with acids proper applications of the chemicals and precise timing were required to prevent ruining the leather. “In staining blacks it is very necessary that plenty of the logwood infusion should be applied to the leather, especially if this is at all lightly tanned. Unless there is plenty of tanning and coloring matter to unite with the iron, the iron will combine with what there is of tannin matter in the leather, and render it brittle and liable to crack If too much iron is used, the leather may be completely ruined.” 4.

Tanners usually made their own tanning solutions, finishes and dyes, however there were also a few commercial black dyes available on the market at the time albeit of questionable quality. “The most that can be said for the best “patent liquid grain” which is now sold is, that it is a great improvement, both as to quality and economy over the “home-made black”, made from pyrolignite of iron” 5.

As can be seen, tanneries were in actuality, little more than specialized chemical factories. Tanners of the period did not have the advantage of product development laboratories, educated chemists or even PH scales as we do today but they nevertheless, held a keen understanding of acids and their dangers honed from centuries of experience. By the mid-nineteenth century hundreds, perhaps thousands of years of effort and experimentation had developed both the tanning and dyeing processes to a fine craftsmanship. For the individual tanneries, these processes were further refined and often closely guarded trade secrets. When applied properly, the result was wonderfully well tanned leather with deep black colors that have stood the test of time. 6.

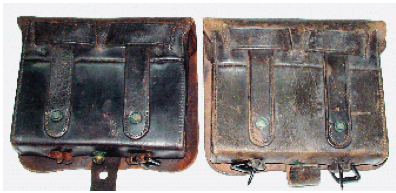

What about the chocolate brown colored leather often seen among other wise legitimate artifacts today? Why are they not black? These leather artifacts were made from hides tanned with Hemlock tree bark rather than the officially sanctioned and, correct Oak bark. Before leather was dyed and finished it was easy to tell the difference between Oak and Hemlock tanning. The two major barks strike unique, entirely different colors. Oak bark always leaves a yellow color whereas hemlock always leaves a reddish skin tone color. However, they further distinguished themselves when dyes were applied. “The most interesting aspect of Hemlock tanned leather and one that created enormous troubles for the Federal Ordnance Department during the war and for collector’s today, was the inert tendency for the dyes of Hemlock tanned leather to fade, often quickly, from black to brown.” 7. Unlike oak bark, hemlock bark tannin does not seriously bond with the iron mordants to change form and thus turn the leather black. After tanning, various specialty dyes were applied that will turn the leather black but usually only temporarily. Unfortunately, the logwood in the leather will eventually oxidize (sometimes very quickly), causing the iron to change form again and return the hemlock leather from black to the chocolate brown we often see today.

Nevertheless, it is clear tanners routinely “cheated” and used hemlock tanning anyway. But why? Hemlock bark had a higher percentage of tannin than Oak and it thus shortened the overall tanning process by a month or more. Another advantage was that Hemlock tanned hides tended to be heavier and therefore brought more money because leather was sold by the pound (until about 1885) rather than by square feet as it is today. Simply put, Hemlock tanned leather was quicker and more profitable to produce but came with its own inherent dyeing problems. Due to the pressures of profit and demand, it is believed that throughout the war many unscrupulous tanners duped the over wrought Ordnance Department inspectors and delivered hemlock tanned leather manipulated to black- if only temporarily. 8.

Then as now, the varieties and applications of leather were infinite. Depending upon intended use, leather had to be strong yet stiff or pliable, thick or thin, smooth or rough, water proof but able to breath. It had to be tough enough for the soles of shoes yet supple enough for clothing. Tanners of the period knew their business very well. First, they knew which type animal hides best fit their specific needs. Through centuries of trial and error they also instinctively knew just the right measure and timing of the chemicals required to properly tan the hide and then to balance the dye formulas with the tannin in the leather to achieve the results they desired. Although most leathers were intended to be consumed in relatively short order and certainly not preserved as artifacts, leather, properly tanned, dyed and cared for can be serviceable and last for many years. In fact, leather artifacts are known to have survived for centuries. There can be no doubt tanning and dying leather was industrial artistry not unlike that of ancient architecture and jewelry. Sadly, due to a variety of reasons including the secretive nature of their trade, much of this knowledge and experience has been lost forever. (Text Box #2)

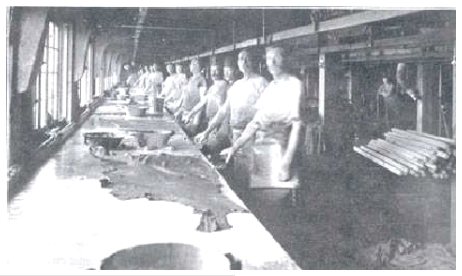

It is worth noting that a typical mid-19th century tannery could not exist today. Tanneries of the period were expansive operations usually found along a creek or river and employing dozens of workers. The process of tanning animal hides into leather was a dirty and dangerous business. Today’s environmental and work place laws would not permit the massive destruction of trees for bark tanning, unfiltered exposure to chemicals by employees and the prolific ground, water and air pollution caused by the leather tanning and dyeing process. Yet despite all of this there is something truly romantic about this lost art form. We cannot duplicate their fine craftsmanship and, we will likely never truly know the depth of their knowledge. However, we can admire their great resourcefulness, ingenuity and skills borne from thousands of years of toil and, fortunately, still enjoy some of their handiwork that survives today.

-30-

TEXT BOX # 1:

TEXT BOX # 2:

|

FROM THE BACKS OF ANIMALS TO THE BATTLEFIELD AND BEYOND Sleeked, waxed and buff leather as used for American military accoutrements and horse equipment was generally made from high quality animal hides. All animal skins are technically classified in the following manner: “hides”; comprising the skins of oxen, horses, cows, bulls and buffalo; “Kips”: consisting of the skins of younger growth of the above animals and, “skins” or, small animals such as dogs, sheep, goats, hogs, seals, etc.

Hides from large cattle and horses were best suited for making most leather although hides of other animals were routinely utilized for specific usages. For example, oxen were considered the best for sole and harness leather while cow and horse hides were often reserved for making high quality saddler’s leather. However, the hides of older cows that have repeatedly calved and lost their elasticity were considered inferior to that of younger heifers. Horse hides made good leather, thongs and belts. Goat skins for ladies shoes. Sheep skins make a spongy, weak leather primarily used for shoe and & boot linings, book binding and trunk trimmings. Goat and deer skins made excellent ladies shoes and gloves while hog skins were almost exclusively used for saddle seats. Bull hides are the least desirable of all being thinner and more flabby than those of oxen or cows but serviceable nonetheless. The nature of the animal’s health and food intake at the time of being killed had a large influence upon the quality of the hide and often the leather itself. Overworked, sick or lean animals or, hides deficient in hair were not well adapted for making good leather but were nonetheless used for lesser quality leather needs. The differences were not easily distinguished except by experienced tanners and thus hides were graded upon purchase. Hides of various kinds were imported from all over the globe in the mid-nineteenth century however, those from the northern latitudes (above the equator) were preferable to those from the South. Interestingly, cattle slaughtered in the colder months tended to give five percent or more leather than hides taken in the summer. |

About the authors: David Jarnagin is part owner of C & D Jarnagin the nation’s largest manufacturers of 18th and 19th century military reenactment clothing and equipment. For over twenty years David’s domain has been the company leather shop where they make authentic cartridge boxes, cap boxes, belts, bayonet scabbards, knapsacks, shoes and more. A passion for the study and experimentation with period leather tanning, dyeing, preservatives, equipment manufacture and of course, the handling of thousands of artifacts have made David uniquely qualified in the subject of 19th century leather processes and leather equipment.

Ken R Knopp, is a financial advisor with Edward Jones Investments and the author of two books on Confederate saddlery, “Confederate Saddles & Horse Equipment” and “Made in the CSA, Saddle Makers of the Confederacy” as well as numerous articles about Civil War saddlery, leather and accoutrements.

Author’s Note: The authors would like to thank collector/author Fred Gaede, Paul D Johnson, author of “Federal Cartridge Boxes” and Doug Kidd of Border Sates Leather for their gracious and immeasurable assistance in the research for this article.

FOOTNOTES:

1. M.C. Lamb, F.C.S., Leather Dressing Including Dyeing, Staining, and Finishing, (London, The Anglo-American Technical Co., Ltd. 1925), pg. 180, 169

2. Ibid, Pgs. 474-475.

3. Ibid, Pgs. 473-474.

4. Ibid, Pgs. 181, 172.

5. Professor H Dussance, Chemist, A New and Complete Treatise on the Arts of Tanning, Currying and Leather Dressing. (Philadelphia, Pa. Henry Carey Baird, T.K. and P.G. Collins Printers, 1867), Pg. 426.

6. Campbell Morfit, The Arts of Tanning, Currying and Leather Dressing, Theoretically and Practically Considered in All Their Details, (Philadelphia, Pa. Henry Carey Baird, 1852)

7. David Jarnagan, Hemlock Leather- The Federal Ordnance Department’s Other War. Journal of the Military Collector & Historian, The Company of Military Historians, Washington DC., Vol. 57, No. 1 — Spring 2005

David Jarnagin & Ken R Knopp, Confederate Leather, Black, Brown, How & Where?, North South Trader’s Civil War, Vol. 32, No. 5, 2007, Pgs.,59-65.

8. Ibid,

9. Campbell Morfit, The Arts of Tanning, Currying and Leather Dressing, Theoretically and Practically Considered in All Their Details, (Philadelphia, Pa. Henry Carey Baird, 1852), pgs, 146-151.